Viminacium Ancient City and Military Camp

Viminacium… It used to be such a radiant town! Monumental temples, wide streets, luxurious villas, extensive baths, an amphitheater… The barbarians devastated it a few years ago and nearly nothing remained of its previous glory. In the town itself, some of the houses and public buildings have been restored, and life is slowly returning, but in these troubled times I did not have confidence in the local people.

Viminacium… It used to be such a radiant town! Monumental temples, wide streets, luxurious villas, extensive baths, an amphitheater… The barbarians devastated it a few years ago and nearly nothing remained of its previous glory. In the town itself, some of the houses and public buildings have been restored, and life is slowly returning, but in these troubled times I did not have confidence in the local people.

(…) In my lifetime, albeit short, I have not seen a town which has such a good location. Roads leading to the south to Naissus and Hellas diverge there; to the east, the via Lederatea, leads to the land of the Dacians. Rivers here are wide and navigable. Travelling along the Danube we would quickly reach Pannonia, Noricum, Raetia, or Dacia. Wherever you look, you see orchards, tilled fields, forests. People are all over the fields, working diligently; one would say that everything is under control. And then, in a moment, when your gaze falls on the ruins of the camp of the Legion VII Claudia and the devastated great temple of the Capitoline Triad, you become aware of the recent destruction. And the military camp was a wonder to behold! Nearly as large as the legionary bases in Castra Regina, or Vetera. Even now, the mighty stone towers can be seen in the distance. And what to say about the Porta Praetoria! Imposing architectural features! I have never seen anything like them!

In the town itself lived a very old master-painter … I cannot remember his name, but I know that in painting frescoes for villas and grave memorials he surpassed his spiritual teacher, the famous Flavius Chrysantius. I felt the sorrow of Caius in the past, and I started to console him with the idea that the town would soon recover fully and that he would enjoy again everything that a man of his knowledge and culture can appreciate.

The reputation of the cultural richness of Viminacium has drawn the attention of not only the domestic but also the international public, who eagerly anticipate that Viminacium will take its rightful place in the first rank of the world’s cultural monuments. It is our expressed intention to uncover this city which has been buried for centuries, to explore it in detail and to interpret the remains for the general public. We sincerely hope that in the years to come Viminacium will become a distinguished symbol of Kostolac and its region and a significant part of the world’s cultural heritage.

The reputation of the cultural richness of Viminacium has drawn the attention of not only the domestic but also the international public, who eagerly anticipate that Viminacium will take its rightful place in the first rank of the world’s cultural monuments. It is our expressed intention to uncover this city which has been buried for centuries, to explore it in detail and to interpret the remains for the general public. We sincerely hope that in the years to come Viminacium will become a distinguished symbol of Kostolac and its region and a significant part of the world’s cultural heritage.

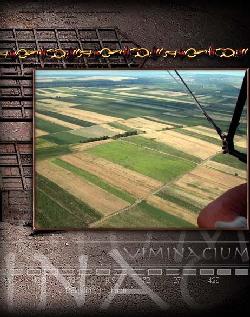

The ancient city of Viminacium is unique in many aspects. It is exceptional with respect to the number of excavated graves (over 13,500 graves have been identified) as well as the quantity of artifacts found in them (over 32,000 objects); it is exceptional in terms of the surface area unencumbered for archaeological investigation (over 1,100 acres/450 hectares for the greater metropolitan area and 540 acres/220 hectares in the city territory proper). The remains of Viminacium extend entirely over cultivated fields, and both fragmentary and sometimes whole ancient artifacts lie scattered on the ground surface. All of these factors had to be taken into consideration in defining the objectives of the Viminacium Project, and, consequently, in devising the methods of exploration in the ancient city and military camp at Viminacium. That is why established scientists in various fields – mathematicians, electrical engineers, geophysicists, geologists, petrologists, and experts in artifical intelligence, remote sensing, three-dimensional modeling and formal analysis – were assembled for this project. A step forward had to be taken to move on from just exploring cemeteries, the cities of the dead, undertaken during the last quarter of the twentieth century, to investigating the city and the military camp proper.

The ancient city of Viminacium is unique in many aspects. It is exceptional with respect to the number of excavated graves (over 13,500 graves have been identified) as well as the quantity of artifacts found in them (over 32,000 objects); it is exceptional in terms of the surface area unencumbered for archaeological investigation (over 1,100 acres/450 hectares for the greater metropolitan area and 540 acres/220 hectares in the city territory proper). The remains of Viminacium extend entirely over cultivated fields, and both fragmentary and sometimes whole ancient artifacts lie scattered on the ground surface. All of these factors had to be taken into consideration in defining the objectives of the Viminacium Project, and, consequently, in devising the methods of exploration in the ancient city and military camp at Viminacium. That is why established scientists in various fields – mathematicians, electrical engineers, geophysicists, geologists, petrologists, and experts in artifical intelligence, remote sensing, three-dimensional modeling and formal analysis – were assembled for this project. A step forward had to be taken to move on from just exploring cemeteries, the cities of the dead, undertaken during the last quarter of the twentieth century, to investigating the city and the military camp proper.

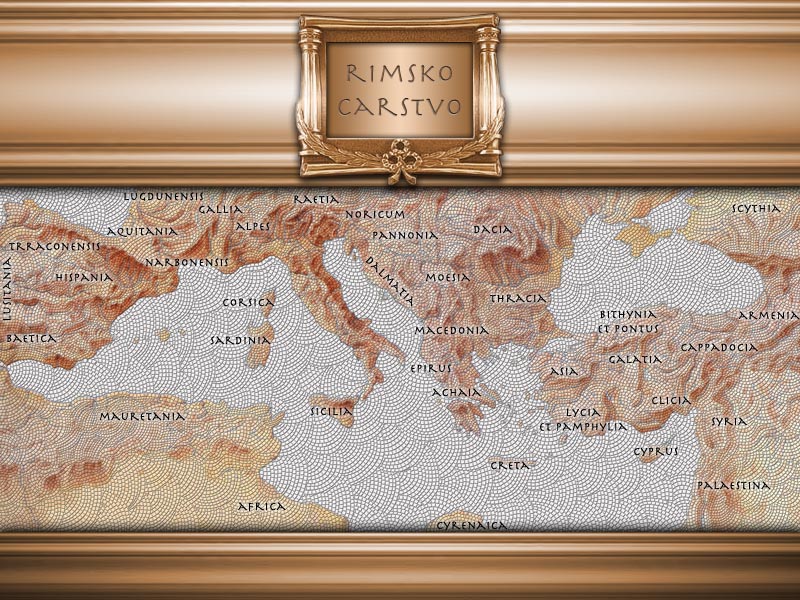

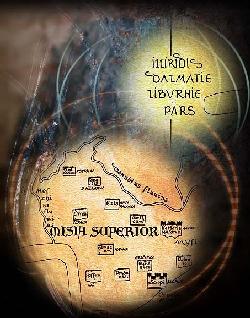

The information gathered to date leads us to conclude that the present-day territories of the villages of Stari Kostolac and Drmno, which are located about 2 miles/3 kilometers from Kostolac and 60 miles/100 kilometers southeast of Belgrade, lie within the limits of the urban territory of the ancient city of Viminacium, the capital of the Roman province of Moesia Superior, which was called Moesia Prima in the late Empire.

The information gathered to date leads us to conclude that the present-day territories of the villages of Stari Kostolac and Drmno, which are located about 2 miles/3 kilometers from Kostolac and 60 miles/100 kilometers southeast of Belgrade, lie within the limits of the urban territory of the ancient city of Viminacium, the capital of the Roman province of Moesia Superior, which was called Moesia Prima in the late Empire.

Historical Sources

The military camp at Viminacium certainly came into existence when the Roman Empire spread to the Balkans, probably during the early decades of the 1st century AD when the Romans first reached the Danube. The discovery of a Celtic necropolis at the “Pećine” site at Viminacium clearly attests to its beginnings on the territory of the Celtic Scordisci. The size and importance of the base originated from a number of factors, among which should certainly be mentioned the rich agricultural hinterland in the Mlava River valley where Viminacium is situated and its important strategic location within the defensive system of the northern frontier of the Empire and also in regional communications and trade networks.

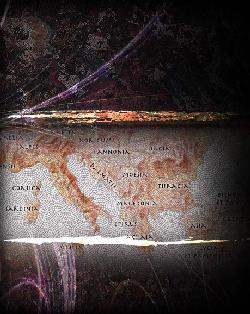

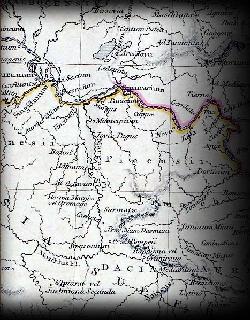

Also important was the location of the legionary camp, and later the city, at a junction of roads linking the northern part of the Balkan peninsula with other parts of the Empire in all directions. One road led south in the Balkan Peninsula through Moesia Superior towards Macedonia and Greece.

A second road, starting in Pannonia, extended along the Danube to the mouth of the river at the Black Sea. Another road connected Viminacium to the north with the Roman province of Dacia through the neighboring camp at Lederata, the modern village of Ram.

Although the primary function of these roads was military and strategic in nature, they were also in constant use by commercial travelers c throughout antiquity and certainly contributed to Viminacium’s role as a prosperous trading and manufacturing center.

The military camp at Viminacium certainly came into existence when the Roman Empire spread to the Balkans, probably during the early decades of the 1st century AD when the Romans first reached the Danube. The discovery of a Celtic necropolis at the “Pećine” site at Viminacium clearly attests to its beginnings on the territory of the Celtic Scordisci. The size and importance of the base originated from a number of factors, among which should certainly be mentioned the rich agricultural hinterland in the Mlava River valley where Viminacium is situated and its important strategic location within the defensive system of the northern frontier of the Empire and also in regional communications and trade networks.

Also important was the location of the legionary camp, and later the city, at a junction of roads linking the northern part of the Balkan peninsula with other parts of the Empire in all directions. One road led south in the Balkan Peninsula through Moesia Superior towards Macedonia and Greece.

A second road, starting in Pannonia, extended along the Danube to the mouth of the river at the Black Sea. Another road connected Viminacium to the north with the Roman province of Dacia through the neighboring camp at Lederata, the modern village of Ram.

Although the primary function of these roads was military and strategic in nature, they were also in constant use by commercial travelers c throughout antiquity and certainly contributed to Viminacium’s role as a prosperous trading and manufacturing center.

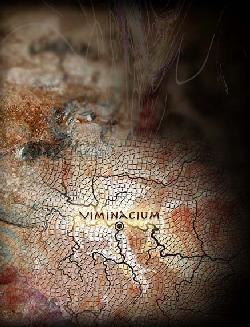

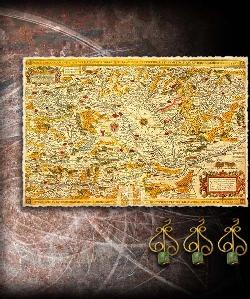

Viminacium’s importance is also reflected in the number of times it is mentioned in ancient literary sources, extending from the 2nd to the 9th century. References are made by Ptolemy, by Iuluis Honorius in his Cosmographia and in Hierocles’ Synecdemus. Viminacium appears in all the known Roman itineraries: the Tabula Peutingeriana, Itinerarium Antonini and Itinerarium Burdigalense.

There are also references in later writers, Theophylactus Simocatta, Theophanes the Confessor and Anastasius Bibliothecarius.

In Latin sources, it is sometimes designated as Viminatio, for example, in the Tabula Peutingeriana(217,5); sometimes as Viminacio or Euminacio, for example in the Itinerarium Antonini Augusti(133,3); and also as civitas Viminacio in the Itinerarium Burdigalense (564).

Viminacium’s importance is also reflected in the number of times it is mentioned in ancient literary sources, extending from the 2nd to the 9th century. References are made by Ptolemy, by Iuluis Honorius in his Cosmographia and in Hierocles’ Synecdemus. Viminacium appears in all the known Roman itineraries: the Tabula Peutingeriana, Itinerarium Antonini and Itinerarium Burdigalense.

There are also references in later writers, Theophylactus Simocatta, Theophanes the Confessor and Anastasius Bibliothecarius.

In Latin sources, it is sometimes designated as Viminatio, for example, in the Tabula Peutingeriana(217,5); sometimes as Viminacio or Euminacio, for example in the Itinerarium Antonini Augusti(133,3); and also as civitas Viminacio in the Itinerarium Burdigalense (564).

In Greek sources, Viminacium is mentioned for the first time in Ptolemy’s Geography (III 9,3), appearing as Uiminakion. On Ptolemy’s map Viminacium features prominently. Priscus (frag. 2, 280 and 8, 305 et passim.) refers to it as Biminakion, and Procopius (De aedif., IV, 5) uses the same designation, while Theophanes (Chron., 24) calls it Bimenakion. In a profane geographical manuscript from the first half of the 6th century, known as Hierocles’ Synecdemus (657,2), Viminacium is designated as Bimenakion metropolis. In the Notitia Dignitatum utriusque imperii, which reflects the situation on the Danube frontier before the year 376, more specifically in the era of Valentinian I and Valens, Viminacium is mentioned as the base of the VII Claudia Legion (legio VII Claudia). The legion is indicated as having a praefectus legionis septimae Claudiae, as well as having a cuneus equitum promotorum. It is also a base for the Danube fleet with a praefectus classis Histicae Viminacio. According to the standard historical interpretation, primarily relying on Priscus’ text, Viminacium perished in a Hunnic attack in 443, which is also documented by finds of coin hoards. The best-known coin found from that period to date is an issue of Theodosius II. Later, in the 9th century, the presbyter-cardinal Anastasius Bibliothecarius, in his work Chronographia Tripartita (23), refers to Viminacium as Viminacium.

In Greek sources, Viminacium is mentioned for the first time in Ptolemy’s Geography (III 9,3), appearing as Uiminakion. On Ptolemy’s map Viminacium features prominently. Priscus (frag. 2, 280 and 8, 305 et passim.) refers to it as Biminakion, and Procopius (De aedif., IV, 5) uses the same designation, while Theophanes (Chron., 24) calls it Bimenakion. In a profane geographical manuscript from the first half of the 6th century, known as Hierocles’ Synecdemus (657,2), Viminacium is designated as Bimenakion metropolis. In the Notitia Dignitatum utriusque imperii, which reflects the situation on the Danube frontier before the year 376, more specifically in the era of Valentinian I and Valens, Viminacium is mentioned as the base of the VII Claudia Legion (legio VII Claudia). The legion is indicated as having a praefectus legionis septimae Claudiae, as well as having a cuneus equitum promotorum. It is also a base for the Danube fleet with a praefectus classis Histicae Viminacio. According to the standard historical interpretation, primarily relying on Priscus’ text, Viminacium perished in a Hunnic attack in 443, which is also documented by finds of coin hoards. The best-known coin found from that period to date is an issue of Theodosius II. Later, in the 9th century, the presbyter-cardinal Anastasius Bibliothecarius, in his work Chronographia Tripartita (23), refers to Viminacium as Viminacium.

In itineraries, Viminacium is always on a crossroads. In the Tabula Peutingeriana, Viminacium is described as a place with connections in all directions. From the west, a road comes from Sirmium via Singidunum and Margum, and continues on eastward and southward. The itineraries mention that Viminacium is 10 miles distant from Margum. To the south, the road went on to Naissus, the first stop on the way being Munecipio (Chronogr. Tripartita, 23) or Municipio (Tab. Peut. and Itin. Ant. 134,1), 18 milia passuum distant from Viminacium. A somewhat different picture is shown in theItinerarium Burdigalense (564, 10) which indicates a mutatio Ad Nonum between Viminacium andMunicipium. The roads to Dacia and down along the Danube did not diverge at Viminacium but at some distance to the east of the city.

According to the Tabula Peutingeriana, the road to Dacia branched off at a distance of 10 miliapassuum from Viminacium via Lederata, then passed through Apofl at 12 milia passuum further on, and on to Arcidava on the left bank at a distance of 12 milia passuum. Lederata ( Byzantine Litterata) is usually taken to be at present-day Ram and across from it, Banatska Palanka, where fortifications secured the Danube crossing.

In itineraries, Viminacium is always on a crossroads. In the Tabula Peutingeriana, Viminacium is described as a place with connections in all directions. From the west, a road comes from Sirmium via Singidunum and Margum, and continues on eastward and southward. The itineraries mention that Viminacium is 10 miles distant from Margum. To the south, the road went on to Naissus, the first stop on the way being Munecipio (Chronogr. Tripartita, 23) or Municipio (Tab. Peut. and Itin. Ant. 134,1), 18 milia passuum distant from Viminacium. A somewhat different picture is shown in theItinerarium Burdigalense (564, 10) which indicates a mutatio Ad Nonum between Viminacium andMunicipium. The roads to Dacia and down along the Danube did not diverge at Viminacium but at some distance to the east of the city.

According to the Tabula Peutingeriana, the road to Dacia branched off at a distance of 10 miliapassuum from Viminacium via Lederata, then passed through Apofl at 12 milia passuum further on, and on to Arcidava on the left bank at a distance of 12 milia passuum. Lederata ( Byzantine Litterata) is usually taken to be at present-day Ram and across from it, Banatska Palanka, where fortifications secured the Danube crossing.

The locations of the camp gates and the cemeteries at Viminacium partially indicate the directions of the Roman roads leading south and east. We know for a fact that the left and right banks of the Mlava River were spanned by a bridge, whose remains were recorded by Jireček, Kanitz and Milićević. Still to this day the local toponym for this site is “Kameniti brod (the stone boat)”. Today, when the water level is low, a stone structure in fact is sometimes visible. To the east of the bridge, on the right bank of the Mlava, traces of an old road have been identified.

Priscus, an author who writes in Greek, tells us that in 441, after they crossed the Danube, the Huns sacked numerous towns and forts, including Viminacium. It is only from Procopius (De aedif., IV, 5) that we learn that the old Viminacium had been razed to the ground and that the Emperor Justinian erected a totally new city. Although Priscus’s text states that the Huns devastated towns and forts, it is not quite clear whether the same fate befell Viminacium. On his part, Procopius explicitly says that “the city was razed to the ground”, but this statement may only refer to an assumed Roman settlement on the left bank of the Mlava, on the ruins of which a Byzantine city could have been built.

An episcopate was definitely located within the city (Hier. Synecdemus 657,2), and Viminacium was under the jurisdiction of Justiniana Prima, as we learn from Nov. IV (De privilegis archiepiscopi Primae Justinianae).

The locations of the camp gates and the cemeteries at Viminacium partially indicate the directions of the Roman roads leading south and east. We know for a fact that the left and right banks of the Mlava River were spanned by a bridge, whose remains were recorded by Jireček, Kanitz and Milićević. Still to this day the local toponym for this site is “Kameniti brod (the stone boat)”. Today, when the water level is low, a stone structure in fact is sometimes visible. To the east of the bridge, on the right bank of the Mlava, traces of an old road have been identified.

Priscus, an author who writes in Greek, tells us that in 441, after they crossed the Danube, the Huns sacked numerous towns and forts, including Viminacium. It is only from Procopius (De aedif., IV, 5) that we learn that the old Viminacium had been razed to the ground and that the Emperor Justinian erected a totally new city. Although Priscus’s text states that the Huns devastated towns and forts, it is not quite clear whether the same fate befell Viminacium. On his part, Procopius explicitly says that “the city was razed to the ground”, but this statement may only refer to an assumed Roman settlement on the left bank of the Mlava, on the ruins of which a Byzantine city could have been built.

An episcopate was definitely located within the city (Hier. Synecdemus 657,2), and Viminacium was under the jurisdiction of Justiniana Prima, as we learn from Nov. IV (De privilegis archiepiscopi Primae Justinianae).

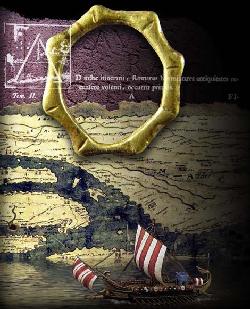

Even though in 584 the Avars invaded Viminacium (Theoph. Sira., Historiae, I 3-V), this event nevertheless did not mark the end of its history. Around 600 A.D., the Byzantine Empire went on the offensive. The Roman army assembled at Viminacium, from where it crossed over to the other bank of the Danube. Interestingly is that the descriptions of these events speak of Viminacium as an island. Theophylactus Simocatta (Hist., VIII, 1), writing in the time of the Emperor Heraclius (610-640), refers to this. The notice that Roman troops had arrived at Viminakion, an island in the River Istar, was repeated by Theophanes the Confessor in the second half of the 8th centuryand by Anastasius Bibliothecarius, a knowledgeable source on the Slavic apostles. This warrants the conclusion that the island and the bend in the Danube played an important strategic role for Viminacium in the early Byzantine, and perhaps even already in the Roman era, as Jireček had assumed long ago.

Even though in 584 the Avars invaded Viminacium (Theoph. Sira., Historiae, I 3-V), this event nevertheless did not mark the end of its history. Around 600 A.D., the Byzantine Empire went on the offensive. The Roman army assembled at Viminacium, from where it crossed over to the other bank of the Danube. Interestingly is that the descriptions of these events speak of Viminacium as an island. Theophylactus Simocatta (Hist., VIII, 1), writing in the time of the Emperor Heraclius (610-640), refers to this. The notice that Roman troops had arrived at Viminakion, an island in the River Istar, was repeated by Theophanes the Confessor in the second half of the 8th centuryand by Anastasius Bibliothecarius, a knowledgeable source on the Slavic apostles. This warrants the conclusion that the island and the bend in the Danube played an important strategic role for Viminacium in the early Byzantine, and perhaps even already in the Roman era, as Jireček had assumed long ago.

We know even less about the medieval city. Bulgarian historians believe that in the Middle Ages Viminacium was a Bulgarian fortified stronghold known under the name of Braničevo. What is important, however, is that the episcopal tradition in the city was preserved in the Middle Ages. This is indicated by the Sigillium primum of Basil II from 1019, in a reference to the Ohrid Archiepiscopate. However, at that time, the mid-12th century travelogue of Odo de Deogilo describes Braničevo as only a miserable little town, Brundusium civitatem pauperculam. In Ansbert, an itinerary writer from the third Crusade (1189-1190), Braničevo appears as Brandiez. At the time of the aggressive expansion of the Latin church during the papacy of Innocent III, Braničevo with its strategic position attracted the attention of the territorially acquisitive pope.

We know even less about the medieval city. Bulgarian historians believe that in the Middle Ages Viminacium was a Bulgarian fortified stronghold known under the name of Braničevo. What is important, however, is that the episcopal tradition in the city was preserved in the Middle Ages. This is indicated by the Sigillium primum of Basil II from 1019, in a reference to the Ohrid Archiepiscopate. However, at that time, the mid-12th century travelogue of Odo de Deogilo describes Braničevo as only a miserable little town, Brundusium civitatem pauperculam. In Ansbert, an itinerary writer from the third Crusade (1189-1190), Braničevo appears as Brandiez. At the time of the aggressive expansion of the Latin church during the papacy of Innocent III, Braničevo with its strategic position attracted the attention of the territorially acquisitive pope.

The question of the Braničevo episcopate is linked to the question of the restoration of Christianity on the Danube in the 9th century and must be viewed against the backdrop of the political and ecclesiastic aspirations of Rome and Constantinople with respect to the lands of the Slavs in general. It is well-known that Basil I and Photius made great efforts to reorganize the church hierarchy in the north. Thus, the Acts of the Constantinople Council from 879 feature Agathonos Moravan among the bishops present. When Methodius was the Morava bishop , P. Dvornik probably rightly concludes that a location at the confluence of the Morava and the Danube rivers was in question. This indicates that the tradition of Roman episcopal seats in Viminacium and Margum had been revived already in the period of the restoration of Christianity.

The question of the Braničevo episcopate is linked to the question of the restoration of Christianity on the Danube in the 9th century and must be viewed against the backdrop of the political and ecclesiastic aspirations of Rome and Constantinople with respect to the lands of the Slavs in general. It is well-known that Basil I and Photius made great efforts to reorganize the church hierarchy in the north. Thus, the Acts of the Constantinople Council from 879 feature Agathonos Moravan among the bishops present. When Methodius was the Morava bishop , P. Dvornik probably rightly concludes that a location at the confluence of the Morava and the Danube rivers was in question. This indicates that the tradition of Roman episcopal seats in Viminacium and Margum had been revived already in the period of the restoration of Christianity.

It is generally accepted that the Legion VII Claudia pia fidelis formed the garrison stationed at Viminacium. In fact, this legion, which was transferred from the Roman province of Dalmatia, earned the epithet pia fidelia in 42 AD when it demonstrated exceptional loyalty during Scribonian’s rebellion in Dalmatia. However, the first legions stationed at Viminacium were the legio IV Scythica and the legio V Macedonica, which by general consensus occurred around 15 AD. According to other scholars , it is also possible that these two legions were transferred to Viminacium in 33/34 AD, during Tiberius’ road-building operations on the Danube. Alternatively the two legions could have been in Viminacium only during the summer period and spent the winters downstream on the Danube or in the hinterland in the legionary camps at Oescus, Ratiaria or Naissus. Tacitus mentions in the Annals that the legions also had their own small winter camps, the so-called hibernae. In any case, by the mid-1st century or some time shortly before that there already was a legion permanently stationed at Viminacium. It is even possible that two legions were stationed at Viminacium into the 80’s AD and Domitian’s campaigns on the Danube.

According to Suetonius, after the rebellions led by Saturninus in 89 of the Legions XIV Gemina and XXI Rapax at their base in Mainz (Mogontiacum), Domitian prohibited the stationing of two legions in a single camp. Up until that time, two or even three legions could be assigned to the same camp.

At Viminacium, after the large-scale archaeological excavations carried out in the last quarter of the 20th century, knowledge of the city slowly emerged from the background of the scattered historical references to reveal a complex of archaeological sites that had experienced vigorous development over the six centuries of its long history.

Given its location and river connections, Viminacium always stood at a junction where cultural influences from the eastern and western parts of the Empire met and interacted. The recovered archaeological material clearly demonstrates an impressively high level of development for the various branches of arts and crafts, and merchants from all over the Roman Empire came to trade their wares here. It appears that the thriving economy of the city, where goods were also produced for export to markets outside the province, also spurred the development of various workshops in the area. In the 4th century some of these workshops produced significant contributions to tomb fresco painting in late antiquity.

The settlement at Viminacium was granted municipal status during Hadrian’s reign around 117 AD, when it was given the title Viminacium municipium Aelium Hadrianum.

It is generally accepted that the Legion VII Claudia pia fidelis formed the garrison stationed at Viminacium. In fact, this legion, which was transferred from the Roman province of Dalmatia, earned the epithet pia fidelia in 42 AD when it demonstrated exceptional loyalty during Scribonian’s rebellion in Dalmatia. However, the first legions stationed at Viminacium were the legio IV Scythica and the legio V Macedonica, which by general consensus occurred around 15 AD. According to other scholars , it is also possible that these two legions were transferred to Viminacium in 33/34 AD, during Tiberius’ road-building operations on the Danube. Alternatively the two legions could have been in Viminacium only during the summer period and spent the winters downstream on the Danube or in the hinterland in the legionary camps at Oescus, Ratiaria or Naissus. Tacitus mentions in the Annals that the legions also had their own small winter camps, the so-called hibernae. In any case, by the mid-1st century or some time shortly before that there already was a legion permanently stationed at Viminacium. It is even possible that two legions were stationed at Viminacium into the 80’s AD and Domitian’s campaigns on the Danube.

According to Suetonius, after the rebellions led by Saturninus in 89 of the Legions XIV Gemina and XXI Rapax at their base in Mainz (Mogontiacum), Domitian prohibited the stationing of two legions in a single camp. Up until that time, two or even three legions could be assigned to the same camp.

At Viminacium, after the large-scale archaeological excavations carried out in the last quarter of the 20th century, knowledge of the city slowly emerged from the background of the scattered historical references to reveal a complex of archaeological sites that had experienced vigorous development over the six centuries of its long history.

Given its location and river connections, Viminacium always stood at a junction where cultural influences from the eastern and western parts of the Empire met and interacted. The recovered archaeological material clearly demonstrates an impressively high level of development for the various branches of arts and crafts, and merchants from all over the Roman Empire came to trade their wares here. It appears that the thriving economy of the city, where goods were also produced for export to markets outside the province, also spurred the development of various workshops in the area. In the 4th century some of these workshops produced significant contributions to tomb fresco painting in late antiquity.

The settlement at Viminacium was granted municipal status during Hadrian’s reign around 117 AD, when it was given the title Viminacium municipium Aelium Hadrianum.

The continued development of Viminacium was briefly interrupted by an epidemic of the plague during Marcus Aurelius’ reign, but indications in the archaeological record show that the economic prosperity of Viminacium was not seriously diminished by the plague because in the early years of the 3rd century commerce was again flourishing.

The continued development of Viminacium was briefly interrupted by an epidemic of the plague during Marcus Aurelius’ reign, but indications in the archaeological record show that the economic prosperity of Viminacium was not seriously diminished by the plague because in the early years of the 3rd century commerce was again flourishing.

There was virtually no Roman emperor who did not pass through Viminacium or spend some time there. Significantly enough, when the Roman Empire started to decline, Viminacium gained in importance, and from the end of the 2nd to the end of the 4th century, for almost two hundred years, Roman emperors even more frequently visited and sojourned at Viminacium because of its exceptional strategic importance. Numerous times in its six hundred year history, for example at the end of the 3rd century, Viminacium played a key role in resolving questions of the disposition of ruling power in the Empire. Among visits by Roman emperors, mention should certainly be made of Hadrian’s residency when hunts were organized for him at Viminacium on two occasions; the Emperor Septimus Severus visited twice; later on other emperors stayed there: Gordian III, Phillip the Arab, Trebonius Gallus, Hostilian, Diocletian, Constantine The Great, Constans I and Julian. Gratian was the last emperor known to have visited Viminacium.

The sojourn of the Emperor Hostilian was of exceptional significance because, as the 5th century writer Zosimus reports, he spent almost an entire year here with his mother Etruscilla. Zosimus is well informed because he draws on earlier authors from the 2nd and 3rd centuries, such as Eutropius, Deuxipus, Aurelius Victor, Pseudo-Aurelius Victor and Eusebius. After the deaths of his father and brother, Hostilian came to Viminacium at the beginning of 251 and organized the deployment of Roman troops along the middle to the lower course of the Danube. The ancient sources state that in November of 251 Hostilian died of the plague, probably at Viminacium.

Today most histories of the Roman Empire make little mention of the Emperor Trajanus Decius and his sons Herennius Etruscus and Hostilian. These men are not numbered among the so-called military emperors, but they do come from good Roman blood lines. Trajanus Decius came from a family of consuls who resided at Sirmium. His son Herennius Etruscus was born in Pannonia between 220 and 230 and, together with his father, was very much involved with the military. Not much is known about Hostilian, but, judging from his coin portraits, he was considerably younger than his brother. He lived in Rome with his mother Herennia Etruscilla and served as a senator, obviously in the shadow of his father and brother. Trajanus Decius elevated both his sons to the rank of Caesar. Although the title ofprinceps iuventutis is attested only for the elder son, Hostilian might have also received it in 251. Usually the title of Augustus was only granted to the elder son; it was conferred on Hostilian only after the death of his father and brother. As emperor, Hostilian bore the title of Imperator Caesar Caius Valens Hostilian Messius Quintus Augustus, and his brother Herennius Etruscus the title of Imperator Caesar Quintus Herennius Etruscus Messius Decius Augustus.

In the 3rd century, during the reign of Gordian III, Viminacium attained colonial status and was granted the right to mint coins.

According to the historical sources, in 284 a decisive battle was fought in the immediate vicinity of Viminacium for supremacy in the empire by the Emperors Diocletian and Carinus.

An important survival from this period is a marble portrait of Carus’s son Carinus, which is stored in the Požarevac Museum.

In the 4th century, Viminacium was an important episcopal seat.

In mid-5th century the city was definitively destroyed by a Hunnic attack. However, it is also possible that the city and the military camp suffered serious damage around 380 from invading Goths. The city was never reconstructed on its original location, and its revival and restoration during Justinian’s reign in the 6th century can only be conjectured on the basis of data provided by Theophylactus Simocatta and the 6th century archaeological remains at the Todića crkva site.

The sojourn of the Emperor Hostilian was of exceptional significance because, as the 5th century writer Zosimus reports, he spent almost an entire year here with his mother Etruscilla. Zosimus is well informed because he draws on earlier authors from the 2nd and 3rd centuries, such as Eutropius, Deuxipus, Aurelius Victor, Pseudo-Aurelius Victor and Eusebius. After the deaths of his father and brother, Hostilian came to Viminacium at the beginning of 251 and organized the deployment of Roman troops along the middle to the lower course of the Danube. The ancient sources state that in November of 251 Hostilian died of the plague, probably at Viminacium.

Today most histories of the Roman Empire make little mention of the Emperor Trajanus Decius and his sons Herennius Etruscus and Hostilian. These men are not numbered among the so-called military emperors, but they do come from good Roman blood lines. Trajanus Decius came from a family of consuls who resided at Sirmium. His son Herennius Etruscus was born in Pannonia between 220 and 230 and, together with his father, was very much involved with the military. Not much is known about Hostilian, but, judging from his coin portraits, he was considerably younger than his brother. He lived in Rome with his mother Herennia Etruscilla and served as a senator, obviously in the shadow of his father and brother. Trajanus Decius elevated both his sons to the rank of Caesar. Although the title ofprinceps iuventutis is attested only for the elder son, Hostilian might have also received it in 251. Usually the title of Augustus was only granted to the elder son; it was conferred on Hostilian only after the death of his father and brother. As emperor, Hostilian bore the title of Imperator Caesar Caius Valens Hostilian Messius Quintus Augustus, and his brother Herennius Etruscus the title of Imperator Caesar Quintus Herennius Etruscus Messius Decius Augustus.

In the 3rd century, during the reign of Gordian III, Viminacium attained colonial status and was granted the right to mint coins.

According to the historical sources, in 284 a decisive battle was fought in the immediate vicinity of Viminacium for supremacy in the empire by the Emperors Diocletian and Carinus.

An important survival from this period is a marble portrait of Carus’s son Carinus, which is stored in the Požarevac Museum.

In the 4th century, Viminacium was an important episcopal seat.

In mid-5th century the city was definitively destroyed by a Hunnic attack. However, it is also possible that the city and the military camp suffered serious damage around 380 from invading Goths. The city was never reconstructed on its original location, and its revival and restoration during Justinian’s reign in the 6th century can only be conjectured on the basis of data provided by Theophylactus Simocatta and the 6th century archaeological remains at the Todića crkva site.

Viminacium and the European Public

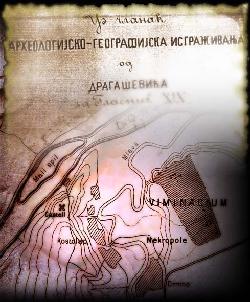

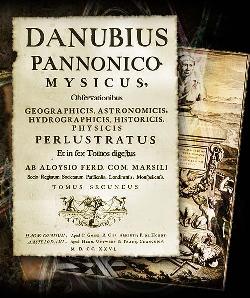

European cultural circles were informed about Viminacium early in the 18th century when Count Marsigli passed through this area; in 1726 in the Hague he published his impressions of his travels in his famous work Danubius Panonico-Mysiscus observationibus and included sketches of Viminacium. The distinguished Count, who was first employed in the service of Vienna and later of Venice, traveled along the Danube in the last decades of the 17th century and left us valuable testimony about and the first map of the ancient city and military camp at Viminacium.

European cultural circles were informed about Viminacium early in the 18th century when Count Marsigli passed through this area; in 1726 in the Hague he published his impressions of his travels in his famous work Danubius Panonico-Mysiscus observationibus and included sketches of Viminacium. The distinguished Count, who was first employed in the service of Vienna and later of Venice, traveled along the Danube in the last decades of the 17th century and left us valuable testimony about and the first map of the ancient city and military camp at Viminacium.

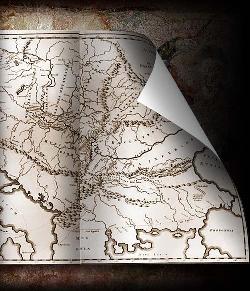

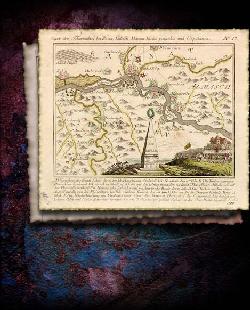

This prominent Count, primarily in the service of Venice, and later, as an officer, engineer and diplomat in the service of Vienna, has left us a valuable testimony about the appearance of Viminacium in the late 17th century and gave us the first basis of the Roman city and military camp. On figure XIII, Marsigli outlines two parts separated by the river Mlava – two fortalitia – one on the right bank of the river Mlava, which he calls Brenincolatz, measuring approximately 360 x 280 meters, and the other on the left bank of Mlava, which he calls Castolatz, measuring approximately 300 x 240 meters. Although the Viminacijum basis causes many concerns of the researchers of Count Marsigli historiography, it is valuable testimony that clarifies and complements the ongoing archaeological excavations, as well as the latest geophysical surveys.

This prominent Count, primarily in the service of Venice, and later, as an officer, engineer and diplomat in the service of Vienna, has left us a valuable testimony about the appearance of Viminacium in the late 17th century and gave us the first basis of the Roman city and military camp. On figure XIII, Marsigli outlines two parts separated by the river Mlava – two fortalitia – one on the right bank of the river Mlava, which he calls Brenincolatz, measuring approximately 360 x 280 meters, and the other on the left bank of Mlava, which he calls Castolatz, measuring approximately 300 x 240 meters. Although the Viminacijum basis causes many concerns of the researchers of Count Marsigli historiography, it is valuable testimony that clarifies and complements the ongoing archaeological excavations, as well as the latest geophysical surveys.

Europeans became aware of this area, and painters and travel writers came to pay homage to the ruins in their work, for example Herring and Bartlett, who produced a series of lithographs with scenic views of the general area. These two painters set out from London for Istanbul but on the way were captivated by the beauty of the Djerdap gorge and its environs and felt compelled to leave behind visual testimony of their visit.

Europeans became aware of this area, and painters and travel writers came to pay homage to the ruins in their work, for example Herring and Bartlett, who produced a series of lithographs with scenic views of the general area. These two painters set out from London for Istanbul but on the way were captivated by the beauty of the Djerdap gorge and its environs and felt compelled to leave behind visual testimony of their visit.

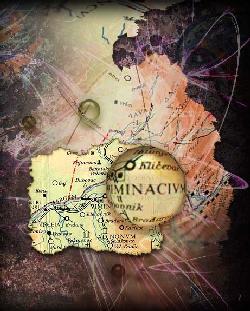

Viminacium was noted on most maps of the area in the period from the 16th to the 19th century. The geographical and political maps of Hungary and neighboring countries, published by the publisher Danit de Meyn and cutter Joanes Deutecum in Amsterdam in 1596, marked Viminacium as Viminallum.

Viminacium was noted on most maps of the area in the period from the 16th to the 19th century. The geographical and political maps of Hungary and neighboring countries, published by the publisher Danit de Meyn and cutter Joanes Deutecum in Amsterdam in 1596, marked Viminacium as Viminallum.

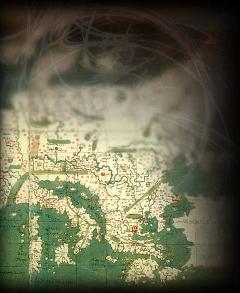

Viminacium was noted on the geographic-administrative map-lithography of the Principality of Serbia, partly in color, made by cutter Anastas Jovanović (1817-1899). The map was published in Belgrade in 1845.

Viminacium was noted on the geographic-administrative map-lithography of the Principality of Serbia, partly in color, made by cutter Anastas Jovanović (1817-1899). The map was published in Belgrade in 1845.

On the engraving, made in copper engraving technique, which is a war map of skirmishes near Rama, Kulč, Smederevska and Banatska Palanka, made by K. Ponheimer, and published by Bartholomew Lopresti (Vienna, 1788), the Viminacium area is marked as Hostelatz.

On the engraving, made in copper engraving technique, which is a war map of skirmishes near Rama, Kulč, Smederevska and Banatska Palanka, made by K. Ponheimer, and published by Bartholomew Lopresti (Vienna, 1788), the Viminacium area is marked as Hostelatz.

On the map from the 18th century Viminacium is named Vieneratz, and map, which shows the Balkan countries and is called Macedonia, Thracia, Illyria, Moesia et Dacia brings Latin name Viminacium.

On the map from the 18th century Viminacium is named Vieneratz, and map, which shows the Balkan countries and is called Macedonia, Thracia, Illyria, Moesia et Dacia brings Latin name Viminacium.

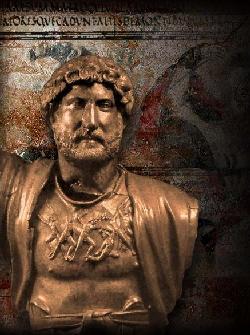

It’s worth to mention the valuable descriptions of Serbian antiquities in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, by Eugene of Savoy, the great military leader and antiquarian, in whose possession was located one of the most important sources of ancient geography – Tabula Peuntigeriana.

It’s worth to mention the valuable descriptions of Serbian antiquities in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, by Eugene of Savoy, the great military leader and antiquarian, in whose possession was located one of the most important sources of ancient geography – Tabula Peuntigeriana.